Gloria Littlemouse brings light to life’s final act

Written by Elizabeth Exline

Gloria Littlemouse, PhD, MSN, RN, learned at an early age how tenuous the line between life and death can be. At 8, she was hospitalized with pneumococcal meningitis, an infectious disease that generally affects babies and toddlers. She watched as friends in her hospital ward passed away. She understood on some level that she’d likely join them.

“I was like, ‘I’m OK if I die.’ I was never worried.”

Destiny, however, had a different plan for her, one in which her brush with death, along with her Navajo heritage and extensive educational and professional experience, would inform her work as a nurse, educator, Caritas coach and end-of-life doula. Hers is a calling few answer because it is so emotionally demanding.

“Who can do this work?” Littlemouse asks. “I can. And I will continue to do it as long as I can.”

Searching for meaning

Littlemouse grew up in Los Angeles to divorced parents who came from different worlds. She wasn’t close to her mother or her mother’s family, remembering them as emotionally distant.

“To this day I can’t remember anything that my mother and I did [together]. … It’s still painful,” she says.

Her father’s side of the family was warmer, especially her paternal grandmother, who taught Littlemouse two vital lessons: how to cook and how to love. “She loved endlessly,” Littlemouse says.

The two sides of her family did not get along, and in many ways, Littlemouse found herself navigating life alone. She got a job at McDonald’s when she was 16, and on her first day she discovered she’d have to clean the grill.

Thus ended her tenure at McDonald’s — and thus began her life’s work: She walked across the street to a nursing home and asked if they were hiring.

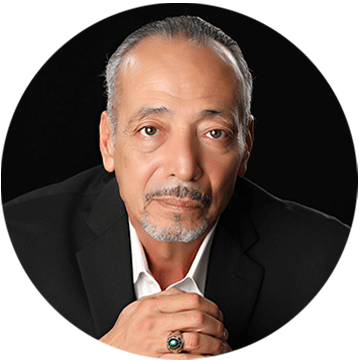

Gloria Littlemouse, MSN, PhD

“I refused to clean the grill at McDonald’s, but I was all right to clean bedpans,” Littlemouse says incredulously. “And let me tell you, back in those days … there were no disposable gloves. We did everything with our bare hands.”

She began to explore this new career path and what it would take to work as a full-time nurse. “The opportunity to take care of a patient, that was my first love,” Littlemouse recalls. “That’s what I fell in love with [about] nursing.”

By 18, she was married (to get out of her family home, she says), and the couple lived off Jell-O and ramen to make ends meet. Eventually, she became a licensed registered nurse and completed her bachelor’s degree — and that’s when things got exciting.

Littlemouse would go on to earn her Master of Science in Nursing at University of Phoenix in 2009, where the online format made it a good fit.

A pandemic-induced detour

For Littlemouse, 2020 brought with it a different set of challenges, and she stepped away from her PhD program. It wasn’t the coursework: She’d excelled in her master’s program and had decided to earn her terminal degree at UOPX as well, a PhD in nursing. (PhD programs have since been retired in favor of practitioner doctoral programs.) But the COVID-19 pandemic had arrived, and suddenly her role as regional director of nursing for a hospice facility seemed less important to her than joining the front lines.

When she was ready to return to the PhD program, however, she discovered it had been retired. She wrote to UOPX, begging to be allowed to finish. She received a letter thanking her for her service and granting her permission to complete the program, which she did in 2022.

John Ramirez, MBA

Dean of Operations, College of Doctoral Studies

“The exception was warranted due to mitigating circumstances beyond her control that prevented her from working on her dissertation,” recalls John Ramirez, dean of operations for the College of Doctoral Studies at University of Phoenix. “During the COVID pandemic, as a healthcare professional, she risked her own well-being to care for her patients and place duty first. … I am extremely proud to be part of the effort to ensure she was granted to exception. I keep the picture she sent me of her at work during the pandemic as a reminder of the exceptional students we have in our college and their selfless service.”

Indeed, Littlemouse’s approach to her career and education embodies both selflessness and a lifelong learning mindset. She currently works as an assistant nursing professor at Vanderbilt University, and she passionately commits herself to a variety of additional endeavors and causes, from presenting and training on behalf of Watson Caring Science Institute to combating human trafficking to earning certification in artificial intelligence.

Navigating life and loss

Littlemouse’s achievements may command a certain level of respect on their own, but combined with her life story, they inspire awe.

Her familial experience, for starters, might’ve been enough to deter most people from pursuing a dream. Her mother’s side of the family eventually disowned her. Friends passed away. Most painful of all was the loss of her children. As she entered her 40s, she discovered she wanted to have a child.

“I realized my ex-husband was the only man I really knew and asked him to father a child with me,” she says. She became pregnant multiple times but miscarried her son, her daughter and then her twins.

Such loss might’ve broken anyone else. For Littlemouse, it became a calling. She had faced death many times, and she came to understand it.

“When you see the emotion at the bedside, that’s love,” she says. “When I see the mother wailing for her child, that’s love. When I see the children crying at the bedside of their parents who are dying, that’s love. So, to me, the best way to explain love is through death.”

Littlemouse became a Caritas coach and a Healing Touch practitioner, training that complements her nursing experience and her spiritual and cultural background. With this foundation, she ushers people toward that which few ever feel truly prepared to face: mortality.

“My grandmother called it a gift, and sometimes I said, ‘I don’t think it’s a gift. I think it’s a burden,’” Littlemouse says. “I literally feel the connectivity to [a patient’s] soul. I feel their pain and suffering. … But I feel the love, and for that reason, I do the work.”

Love, at the end of the day, is the guiding force behind her life and work, whether she’s presiding over someone’s passing or helping the living face life.

One day, for example, Dr. Littlemouse recalls a friend calling to ask her to help her son. He’d been in the military, her friend said, and had come home but was suicidal. When he arrived at Littlemouse’s house, the effect was immediate.

“I saw death walking through my door,” she says. “I saw this huge black shadow on him, like literally sitting on him, smothering him.”

Calling upon her Diné (Navajo) ancestors, Littlemouse began to move energy in and around him. By the time she finished, he sat up, hugged her and cried. A month later, he appeared on her doorstep with flowers, deeply transformed and profoundly grateful.

“I always tell people who ask, ‘What can I do?’ to just be love out there. To me, love is everything,” she says.

Stepping into the future

Today, Littlemouse still works occasionally with private clients outside of her professorship, and she advocates for love, inclusion and healing in multiple capacities, whether as a presenter, trainer or educator.

Whereas some people overcome great odds to find their traditional happy ending, Dr. Littlemouse’s story is a little different. Her happy ending is a work in progress, always with her and yet unlike anyone else’s.

More profoundly, it appears to be deeply intertwined with the fate of others.

“You know, I just send it out there to whoever needs love,” she says. “Little things that we do with great love — that brings change to our world.”

Meet other Phoenixes like Gloria. Make connections, build relationships and be part of a growing community. Join a chapter .

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elizabeth Exline has been telling stories ever since she won a writing contest in third grade. She's covered design and architecture, travel, lifestyle content and a host of other topics for national, regional, local and brand publications. Additionally, she's worked in content development for Marriott International and manuscript development for a variety of authors.

Read more articles like this: