What is a first-generation college student?

Written by Elizabeth Exline

When Joshua Grove began his Bachelor of Science in Business with a General Management Certificate program at University of Phoenix (UOPX), he faced a multitude of challenges.

He was a first-generation college student with little understanding of the application process or university experience and no one to learn from. He’d never written an essay in his life, he says, and didn’t know more than five “useful buttons” on a calculator. He assumed he’d spend his life working in manual labor because college was “for other people.”

Getting ready for and applying to college can seem daunting to a first-generation college student with no one to turn to for help. And that’s just the first step. The actual college experience presents a unique set of barriers to first-gen students, which is reflected in graduation statistics.

Six years after entering postsecondary education, only 20% of first-generation college students will have earned a bachelor’s degree, according to the Center for First-Generation Student Success . Compare that to the 49% of continuing-generation students who statistically attain a bachelor’s degree after the same amount of time.

First-generation college students, in other words, have to start from scratch in a lot of areas, from figuring out how to pay for college to learning how (and whom) to ask for help along the way.

Here, we break down what the first-gen college experience is really like — and how to succeed.

What does 'first-generation college student' mean?

Even the definition of the term is up for debate, which may reflect the challenges and opportunities that come with being a first-generation college student.

Is a first-gen student one whose parents and siblings never attended college? Or a student who has just one parent who never attended college? Or a student who had one or two parents who attended but didn’t complete college? What about students whose parents earned an associate degree but not a bachelor’s?

According to the Center for First-Generation Student Success (and the federal government, which it cites), the definition of a first-generation college student is a person whose “biological parents did not complete a four-year college degree.”

Like Grove, Kalen Baliles found himself in this group when he took a job with a gas and oil company after high school. His dad had been in the Air Force and had completed some college courses but never earned a degree. His mom didn’t attend college.

Yet the expectation to prioritize his education was still there for Baliles. In high school, he recalls, he had to keep up his grades to play sports or go out with friends.

Those turned out to be seeds that flourished by the time Baliles was holding down a full-time job in 2012. “It was a dream to go back and actually finish [college] and show my family, ‘Hey, we can do this,’” the UOPX alumnus says.

Challenges faced by first-generation college students

The data on first-generation college students paints a picture that is concerning. Beyond the dismal graduation rates cited above, Pew Research Center reported the following statistics in May 2021:

- 70% of adults who have a parent with at least a bachelor’s degree go on to earn a bachelor’s degree themselves. Only 26% achieve this when neither parent has a bachelor’s degree.

- The median household income is $135,800 when headed by a person with a bachelor’s degree who also has a parent with at least a bachelor’s degree. For first-generation bachelor’s-degree holders, the median household income is $99,600.

- The median wealth is $244,500 for heads of households who have a bachelor’s degree and who have at least one parent who holds a bachelor’s degree (or better). For first-generation bachelor’s-degree holders, the median wealth is $152,000.

How much education your parents have, in other words, greatly predicts how much education you will have. And education directly affects your earning potential .

It’s also worth noting that, even though first-generation college graduates may earn less than continuing-generation graduates, they’re still earning more than the national annual mean wage, which was $65,470 in May 2023, according the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

So, what specific challenges do first-generation college students face? And how can they overcome them? Read on.

Salary ranges are not specific to students or graduates of University of Phoenix. Actual outcomes vary based on multiple factors, including prior work experience, geographic location and other factors specific to the individual. University of Phoenix does not guarantee employment, salary level or career advancement. BLS data is geographically based. Information for a specific state/city can be researched on the BLS website.

Limited access to support

While being the first in your family to attend college can be a source of pride, it can also cause some unexpected rifts. Grove, for example, encountered this in his own family where he describes having to overcome an unwarranted stigma. In his family, a four-year degree didn’t automatically command respect, despite his feeling proud of his accomplishment and the hard work it took to earn his degree.

This situation is not uncommon, although students may encounter variations. Baliles, for instance, had a very supportive family — his kids began to take school more seriously when he started college, and his wife decided to go back to school and get her Bachelor of Science in Nursing — but he didn’t have anyone to reach out to when he had a math question

or needed help with his accounting class.

Other students might face feelings of confusion or even guilt for leaving behind their family (and their family’s way of life). This is especially true among immigrant families in which the student serves as a translator and intermediary between the family and their new country.

Pamela Roggeman, EdD, dean of the College of Education at UOPX, puts this concept in a real-world context. She notes how family members are often proud of the relative who gets into college, but they don’t always offer the day-to-day support that person needs to succeed. “Will they offer childcare in order for you to meet a group deadline?” she asks. “Will they understand when you miss another birthday party or family reunion?”

A lot of times, there can be tension. Establishing boundaries can help, and so can open communication when both parties truly want to see the student succeed.

Baliles’ situation highlights another solution. “Develop a network,” he advises. He and three other classmates discovered in an operations management course that they worked well together, so they reached out to their academic advisors to enroll in future classes together.

Resources and financial constraints

Not all first-generation college students are low-income students, but many of them lack the financial resources and acumen of continuing-generation students. According to a 2019 Pew Research Center report on first-generation college graduates, the median adjusted household income was much higher for those whose parents had a college degree. Looking at all households, those with no parents with a bachelor’s degree had a median income ($65,200) about a third less than those with a parent with a bachelor’s degree or additional higher education ($100,900).

That means first-gen students not only have to figure out how to pay for college , but they also have to learn the language

of financial aid and scholarships.

Grove felt the impact of this lack of knowledge when he started college. “Financial aid and disbursements were a challenge I was unprepared for,” he recalls.

A lack of financial resources can also affect first-generation students’ overall college experience. It may impact the number of colleges they can apply to (due to application fees), and it may affect how they spend their free time. After all, between classes and working, there’s little time or money left for student organizations and clubs.

Beyond financial resources, many first-generation students often don’t know about scholarly resources available to them, such as tutoring , counseling

and technology assistance

. Such resources can help improve a student’s academic success — and accessing them may just be a matter of knowing where to look.

Lack of time

Time is in short supply for most working adults. For working adults who happen to be attending college — and are the first generation to do so — even more so. One unexpected consequence of this dearth might be a student’s inability to seek internships that can lead to job opportunities down the road.

“They can’t afford to work for free, and their parents do not have professional networks,” explains Linda Banks-Santilli in her article “Living a double life .”

Mentorship, in fact, is a critical service many first-generation college students live without, often to their detriment. This can impact their career opportunities after graduation and even their application to college in the first place.

Mentorship can offer other advantages, too, notes U.S. News & World Report . Understanding how to balance work and school, knowing where to look for scholarships and figuring out how to get involved outside of the classroom are all valuable skills that need to be learned.

One way to overcome the work-school-life balance is to find a school that fits your needs. University of Phoenix, for example, offers multiple start dates throughout the year as well as online classes with 24/7 access to course materials. Students can essentially learn when it works for them.

Recognized student organizations (RSOs) at University of Phoenix are another resource. Designed with the working adult in mind, RSOs provide a sense of belonging and support for students as they balance academic, professional, familial and personal responsibilities. RSOs are also the bridge between the classroom and careers, helping students “demonstrate their newfound skills and use them for professional enrichment.”

Tips for first-generation college students

When it comes to finding success as a first-generation college student, here’s how to stack the deck in your favor.

1. Find a school that supports you with dedicated resources for students . “Really take a look at the support that your institution is offering,” Roggeman advises. “First-generation students are the ones who really need [resources like] technology resources and extra tutoring when it comes to those core subject areas that they haven’t dipped into in a long time. ‘How do I write? How do I do math?’”

2. Connect with other first-gen students. No one understands your struggles and triumphs quite like other first-generation college students. By helping one another throughout the process, everyone goes further and you combat the isolation that sometimes pervades a new experience, Roggeman says.

If you can’t find that network in class, get online. There are plenty of organizations dedicated to first-generation student success, including I’m First and America Needs You

.

3. Leverage the resources you have. “I took advantage of Phoenix Connect, the student library, academic and financial counseling, student discounts and peer groups throughout my studies,” Grove recalls.

Baliles also relied on school resources during his education. In addition to being in regular contact with his academic advisor, he checked out UOPX’s Career Services from day one. “I’ve revamped my resumé,” he says, “and I finally know how to write a good cover letter!”

4. Join an RSO. This can help you gain access to opportunities for personal growth, cultivate leadership ability, access mentorship and scholarships, and develop career plans.

5. Stick to a schedule. Organization spells success when it comes to college, and that’s true for first-gen and continuing-generation students alike. Baliles, for example, got up at 3 a.m. every other day to read coursework. Then, after his regular workday, he’d focus on his school papers and team projects. By dedicating three days a week to this schedule, he was able to successfully complete his program.

6. Develop your self-advocacy gene. College isn’t high school. When you’re taking class with 100 other students, no one will notice if you regularly skip it or drop out altogether. “You’re going to have to fight to stay in,” Roggeman says. Be prepared.

How to pay for college

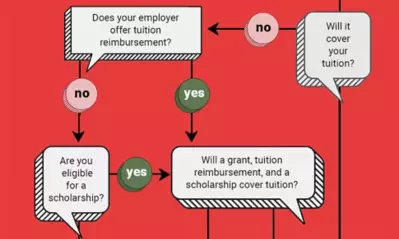

Paying for college can feel like its own education. Between navigating financial aid and writing scholarship essays , there’s plenty to learn.

The good news about paying for college is there are lots of options. Students can pursue financial aid in the form of loans and grants, and they can explore scholarship opportunities both at their school of choice and externally. (There are scholarships out there

expressly for first-generation college students.)

Often, students combine two or three of these approaches to cover their costs. The best place to start is by filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid

(FAFSA®) and researching scholarships online.

First-generation college students may face a bevy of challenges from time management to finances, but the experts all agree on one thing: First-gen students are smart enough to succeed. They just need a road map to get started.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Elizabeth Exline has been telling stories ever since she won a writing contest in third grade. She's covered design and architecture, travel, lifestyle content and a host of other topics for national, regional, local and brand publications. Additionally, she's worked in content development for Marriott International and manuscript development for a variety of authors.

This article has been vetted by University of Phoenix's editorial advisory committee.

Read more about our editorial process.

Read more articles like this: