What the future of nursing looks like after the COVID-19 pandemic

At a glance

- The COVID-19 pandemic upended the healthcare industry, creating lasting impacts and questions about the future of nursing.

- A rise in travel nursing and an emphasis on the mental and physical health of caregivers are trends to come out of recent impacts to the nursing workforce.

- Burnout, workforce shortages and poor environments are just a few of the factors contributing to many nurses considering new roles in healthcare or leaving the profession altogether.

- University of Phoenix offers healthcare and nursing degrees that can help registered nurses explore new career paths.

The future of nursing: What's next?

The pandemic upended a lot of institutions we once took for granted. Gyms closed. Restaurants switched to takeout (when they didn’t close completely). Anything that could be delivered was.

But today, as the dust settles and people finally drop the “new” from “normal,” it’s time to take stock of where we are. And one profession emerges as impacted possibly more than any other: nursing.

Kathy Rupp, PhD, MSNL, RN, CNE, is an associate dean in the College of Nursing at University of Phoenix. Nursing, she says, is still one of the most trusted professions in the world. Yet the field underwent a roller coaster of change during the pandemic, from nurses being revered as heroes to feeling overworked and underappreciated as hospitals across the country were overwhelmed.

Now, as the pandemic slowly (slowly!) recedes in the rearview mirror, everyone is left wondering: What does the future of nursing look like?

The gains

One trend to come out of the pandemic is the way it shifted people’s awareness of nurses’ capabilities. Nurses may have always been trusted, but they haven’t always been considered co-collaborators in medical settings.

According to Rupp, however, the pandemic changed that.

“It has shown that nurses can be flexible and versatile and that we can go into any situation and succeed,” Rupp says.

Nurses are taking those qualities on the road. One of the biggest post-pandemic trends in the profession has been the rise in travel nursing.

The Nurse Licensure Compact, which allows a nurse to hold one license and practice in multiple states, opened the doors to the travel nursing path.

Rupp herself came to Arizona as a travel nurse in 2000. Back then, travel nurses enjoyed a small bump in salary to compensate for the inconvenience of moving around. Post-pandemic, salaries have increased enough to attract more nurses into the travel nursing fold.

“I don’t think the money is going to stay,” Rupp concedes. “I think the money is going to self-regulate back to what it was before.”

In fact, there have been recent calls to investigate claims of price gouging among agencies that staff travel nurses. The accusation? Those agencies have charged hospitals two to three times what was charged before the pandemic.

Another pandemic trend has been the realization among nurses that it’s important to take care of more than just patient health.

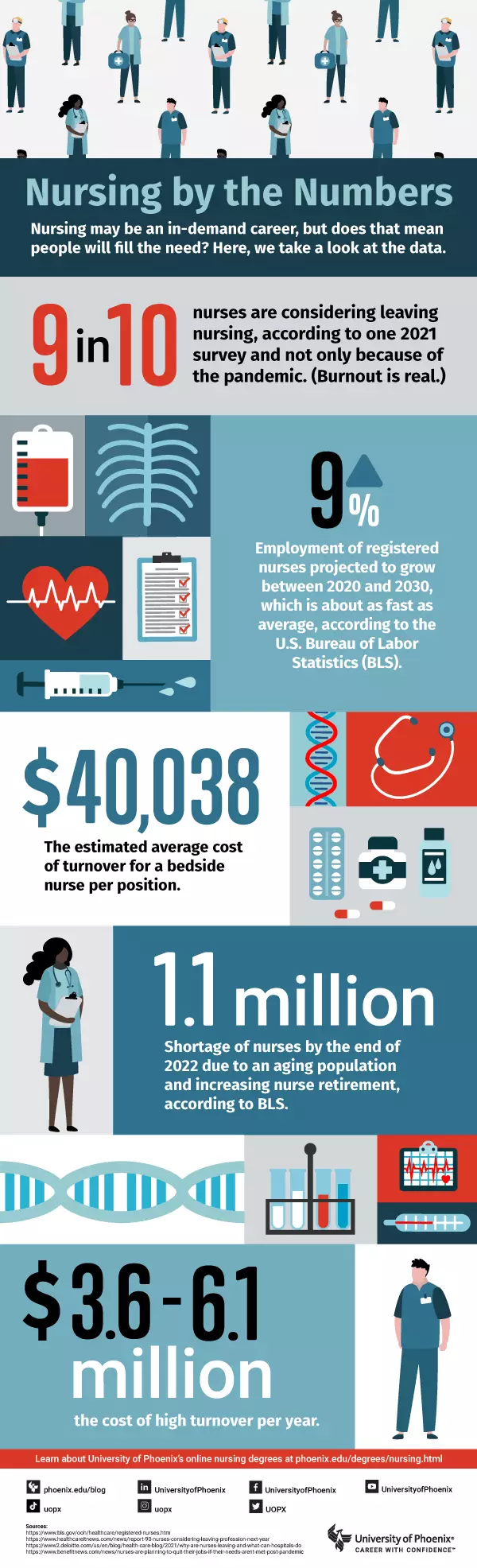

In fact, a contributing factor to the nursing shortage experienced during the pandemic was a rise in nurse burnout. According to a Nursing CE Central’s 2021 nursing burnout survey, 95% of surveyed nurses experienced burnout within the past three years. As a result, nearly 48% of them said they were looking for a less stressful nursing position or to leave the profession altogether.

Dina Shepard, a registered nurse and University of Phoenix alumna, says she has experienced this recently where she works. Although burnout seems far-reaching, Shepard says it has also helped create a greater community among the nursing workforce.

read similar articles

What is a travel nurse?

Shepard has been a nurse for nearly 25 years, most of it in obstetrics, and her observations corroborate those of Rupp, whose background is in critical care nursing and nursing leadership and education.

“We’re caregivers,” Rupp says, “and it’s really hard to care for yourself when you’re so invested in caring for other people.”

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has caused a lot of nurses to reevaluate what they want out of their careers, including options that are less stressful and risky than bedside care and potentially better for their overall health.

The losses

While this shift away from patient-facing roles may be good for nurses, it may not be so good for nursing as a profession or, by extension, hospitals and patients. According to a November 2021 Hospital IQ survey, 90% of responding registered nurses said they considered leaving the profession in a year unless changes were made. Of that group, 71% of RNs with more than 15 years of experience were thinking about leaving within a few months.

“Nursing has changed drastically because a lot of senior nurses have retired or just left the hospital setting altogether,” Shepard says.

Part of this was because of the real fear about nursing during COVID. As Rupp points out, “I know [my daughter, who is an ER nurse] is thinking, ‘It’s my duty. I became a nurse to do this. I have to do my shifts, but I’m scared.’”

Choosing between their patients’ lives and their own lives and health was undoubtedly enough for some nurses to rethink their career choice. For others, the pandemic only exacerbated issues that had long been boiling below the surface. Chief among these? Patient load.

Determining a standard nurse-to-patient ratio is more difficult than it sounds. The standard varies among states, hospitals and even departments. In fact, California is the only state to specify by law a nurse-to-patient ratio. In intensive care, that ratio is one nurse for every two patients. In the ER, it’s one nurse for every four patients.

The ideals may not have been met during the pandemic, however. The same Hospital IQ survey found that 45% of respondents experienced a 5:1 or higher patient-to-nurse ratio across shifts. Further, 96% of critical care nurses and 84% of emergency room nurses surveyed reported that they experienced a 4:1 ratio or higher.

Caring for more patients is one thing. Doing so with limited resources is another. The pandemic’s effects could also be felt in education. During the worst of COVID, nursing students had to complete their clinical hours via simulation since on-site opportunities in hospitals evaporated with the lockdowns.

The future of nursing: Change ahead!

Determining which transformations in nursing are here to stay can feel like more of an art than a science. Will the focus on public health continue to dominate five years from now? What about all the new nurses who had their credentials expedited during the pandemic? Will senior nurses resent having to train so many from the ground up? Will there even be enough senior nurses to do so?

Questions abound, but virtually everyone agrees on the expanded role of telemedicine in nursing.

“What we’ve discovered is you don’t have to put patients in a waiting room and have them wait to be seen by a provider,” Rupp says. “[Telemedicine] works. It is cost effective, and it creates access for patients to get healthcare where they wouldn’t necessarily have had it.”

Telemedicine is ideal for people in rural areas, as well as elderly and immunocompromised patients. “I think telehealth is one of those things that is here to stay as far as nursing,” Rupp adds.

Another ongoing change? Exploring new roles in nursing. Travel nursing is part of this, but so is exploring non-patient-facing roles in administration and related fields.

“Nurses are considering leaving the bedside in droves,” Rupp says. “Some of them are leaving for administrative roles. Some of them are leaving for more provider type roles, like nurse practitioners, and others are leaving the profession completely, which is too bad because all that does is worsen our nursing shortage and educator shortage.”

The impact on education can be felt accordingly. Some registered nurses are opting to work more rather than go back to school to get a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, Rupp acknowledges.

But others who want to exit bedside care may find education an ideal path to a new role in administration or elsewhere.

Nursing still has plenty to recommend it. There’s job security and job flexibility. There’s opportunity for growth and continuing education. But even with those advantages, the question remains: What does the future of nursing look like? Only time will tell.

want to read more like this?